Indigenous Period – 10,000 BCE – 1856 CE

Before it was permanently occupied, the San Luis Valley was traversed by a wide range of indigenous people, from Folsom cultures thousands of years ago to Apache, Navajo, Pueblo, and Ute peoples in more recent times. Owing to its broad expanse, extreme weather, and multiple mountain passes, the San Luis Valley was pre-historically used more as a corridor than as a site of permanent community. Human presence is documented by projectile points left by Folsom people over 10,000 years ago; archaeological evidence suggests that those people, as well as later Archaic cultures, followed large game such as bison into the valley on seasonal treks between the mountains and plains.

In the 15th century, many tribes regularly occupied the valley, hunting bison and other large game and gathering roots, nuts, and berries along its main waterways. Over the next several hundred years, the San Luis Valley was used and traversed by bands of Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, and Cheyenne, and was frequently occupied by three distinct bands of Utes: the Tabeguache, Mouache, and Capote. The Ute Trail became known as the Spanish Trail used by Spanish explorers as early as the fifteenth century. When Santa Fe was established as the northern capital of the Spanish colonies, Spaniards captured Native Americans as slave laborers to work in their fields and homes. Around 1637 Ute captives escaping from the Spanish in Santa Fe fled, taking with them Spanish horses, thus making the Utes one of the first Native American tribes to acquire the horse.

Eventually removed from the valley by a series of disastrous treaties, the Ute and others largely left in the 1850s, leaving the valley open for outside settlers. After the San Luis Valley was ceded to the United States by Mexico, Hispanic settlers started to make their way north. Making a home for themselves in the valley they founded the town of San Luis in 1851. Later, to protect the valley from hostile Indians, a fort was established by the United States Army in the present-day Fort Garland, in 1852. Bands of Apache continued to camp and travel in the area until and even after their reservation was established across the Rio Grande in Dulce in 1887.

Spanish Period, c. 1598–1821

In 1540 Francisco Vásquez de Coronado set out from Compostela in New Spain (Mexico) and conquered native pueblos near modern-day Santa Fe, claiming all lands to the north, including Colorado, for the Kingdom of Spain. At least twelve recorded expeditions into present-day Colorado occurred between 1593 and 1780. Several lack documentation; however, they are mentioned by later expeditions. The initial visit to the region of present-day Colorado was an unauthorized expedition led by Francisco Leyva de Bonilla and Antonio Gutierrez de Humana in 1593. During the expedition, Humana murdered Bonilla, and all but one of the remaining members of the group were killed somewhere in the vicinity of the Purgatoire River.

In 1601, Juan de Oñate explored the region in an effort to locate evidence of the earlier Humana and Bonilla expedition, and discovered the Arkansas River, which he named El Rio de San Francisco. In northern New Mexico, he established two towns, San Juan de los Caballeros and San Gabriel de Yunque. Hearing about plentiful game to the north in the San Luis Valley, Oñate sent an expedition there to hunt bison. The party came across a village of about fifty Ute lodges; the Utes greeted them warmly, and some of the Ute men volunteered to help the inexperienced Spaniards hunt bison. The Spaniards botched the hunt, but they returned back to their own villages knowing that they might at least have willing trade partners to the north. The Spaniards’ relations with the Utes remained friendly until the 1630s, when Spaniards attacked a band and took about eighty Utes as slaves. Thereafter, Utes began raiding Spanish parties and communities for livestock and goods.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the San Luis Valley remained largely indigenous, not even a remote outpost of the Spanish Empire. Comanche raids on New Mexican communities increased during the eighteenth century; in 1779 the Spanish war party of Juan Bautista de Anza picked up Ute and Jicarilla Apache warriors in the valley on its way to fight the Comanche leader Cuerno Verde.

The first American description of the San Luis Valley was offered by the explorer Zebulon Pike in 1807. After trying and failing to climb Pikes Peak, the expedition moved southwest into Spanish territory in the San Luis Valley. “The great and lofty mountains . . . seemed to surround the luxuriant vale, crowned with perennial flowers, like a terrestrial paradise, shut out from the view of man,” Pike wrote in his journal. Fearing attacks by Spaniards and Indians, Pike had his men build a stockade on the banks of Conejos Creek. Despite his precautions, Pike and his men were arrested by Spanish dragoons and imprisoned in Santa Fé for several months.

After Pike, French, American, and Mexican fur traders traversed the San Luis Valley on their way to the beaver-laden mountains and the regional trade nexus of Taos. In the valley itself, small trading camps sprung up along Saguache Creek (from the Ute word Saguguachipa, “blue water”) below Poncha Pass.

Mexican Period: 1821–1836

After winning independence from Spain in 1821, the new nation of Mexico used land grants to encourage the occupation of its northern frontier as a bulwark against rising American influence in the Southwest. All seven of Colorado’s land grants were awarded by the Mexican government after 1821. In 1833 the Mexican government awarded the Conejos Grant, roughly spanning land between the Rio Grande and Conejos Creek near present-day Alamosa, to fifty families. However, Navajo drove off the would-be settlers.

Other Mexican land grants in the valley included the Beaubien-Miranda Grant (later known as the Maxwell), the Luis Maria Baca Grant No. 4, and the Sangre de Cristo Grant, which later became Costilla County and part of northern New Mexico. These were all issued in 1843–44 but were not settled until several years later due to Indigenous resistance and the outbreak of the Mexican-American War (1846–48).

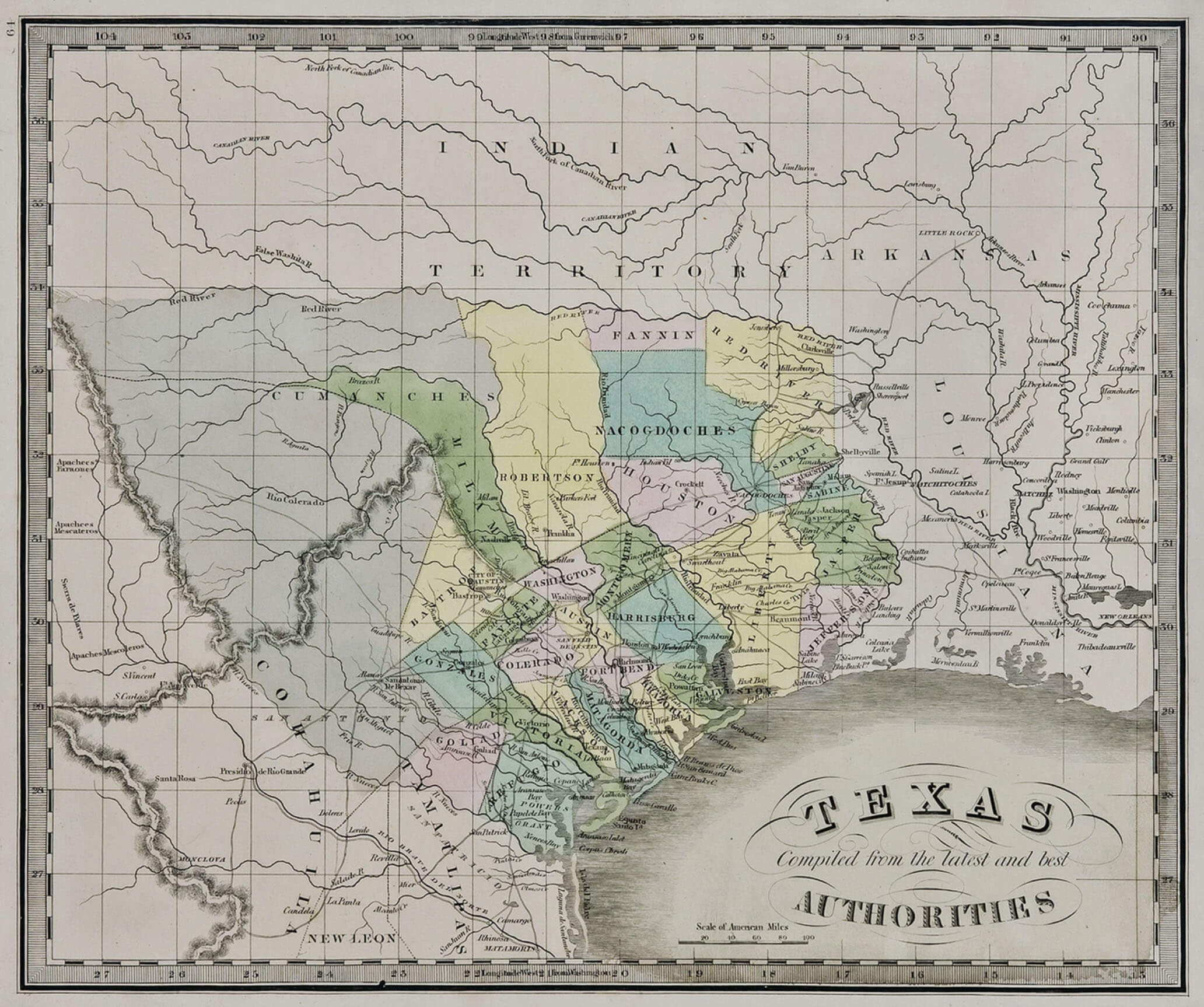

Republic of Texas Period, c. 1836 – 1845

Except for the possible claim of the Rio Grande as the western boundary for the Louisiana purchase, the western boundary of Texas had no significance in international relations and practically no mention in Mexican interstate relations before Texas independence in 1836. In 1721 the Medina River was considered the boundary between Texas and Coahuila; in 1811 the Nueces River was the boundary between Texas and Tamaulipas. Provisions of the secret treaty of Velasco, which bound the Mexican army of Santa Anna to retreat beyond the Rio Grande and Texas not to claim land beyond that river, was the beginning of the Texas claim to the Rio Grande as the western boundary. On April 21, 1836, the forces of the Mexican army under General Santa Anna were handed a decisive defeat by the Texans at San Jacinto. Dressed as a common soldier, Santa Anna attempted to flee, but was taken prisoner the following day. On May 14, Santa Anna signed two peace treaties with interim Texas president David G. Burnet. The public treaty consisted of ten articles; a second, secret treaty consisted of six additional articles. The secret agreement was to be carried out when the public treaty had been fulfilled.

The public treaty provided that hostilities would cease, and that Santa Anna would withdraw his forces below the Rio Grande and not take up arms again against Texas. In addition, he also pledged to restore property that had been confiscated by the Mexicans. Both sides promised to exchange prisoners on an equal basis. The Texans would send Santa Anna back to Mexico and would not pursue the retreating Mexican troops. In the secret agreement, the Texans agreed to release Santa Anna immediately in exchange for his pledge to use his influence to secure Mexican recognition of Texas independence. Santa Anna would not only withdraw all troops and not take up arms against Texas again, but would arrange for a favorable reception by the Mexican government of a Texas mission and a treaty of commerce. The Texas border would be the Rio Grande.

On May 26, General Vicente Filisola began withdrawing Mexican troops in fulfillment of the public treaty. However, the Texas army blocked Santa Anna’s release by the Texas government. Moreover, the Mexican government refused to accept the treaties on the grounds that Santa Anna had signed them as a captive. Since the treaties had now been violated by both sides, they never took effect. Mexico was not to recognize Texas independence until the U.S.-Mexican War was settled by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

On December 19, 1836, the First Congress of the Republic of Texas declared the southern and western boundary of Texas to be the Rio Grande from its mouth to its source and thence a line due north to the forty-second parallel. The Texan Santa Fe expedition of 1841 was an unsuccessful attempt to assert Texas authority in the New Mexico area embraced in that land claim.

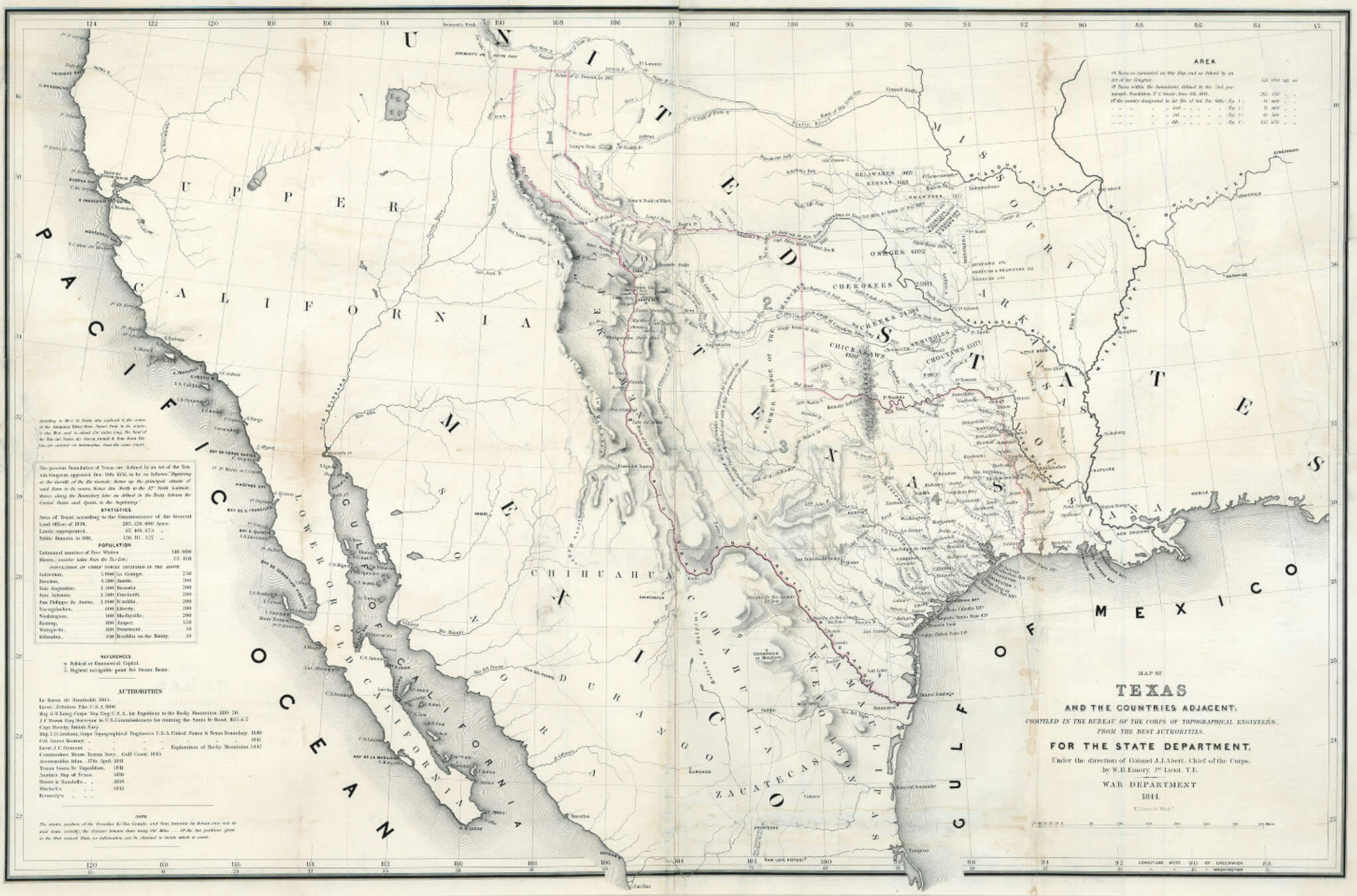

Under the threat of war, the United States had refrained from annexing Texas after the latter won independence from Mexico in 1836. But in 1844, President John Tyler (1790-1862) restarted negotiations with the Republic of Texas, culminating with a treaty, and annexation in 1845. Texas claimed the same western limits after annexation as before, including lands in Colorado. The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) affirmed the Rio Grande boundary to El Paso as the international boundary, but the Texas claim to Parts of Wyoming, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico, then occupied by United States troops, remained in dispute. Texas decreed a county, Santa Fe County, to include part of the area, but the people of New Mexico protested the Texas claim. After prolonged debate in Congress and the Texas newspapers and near-armed dispute, an adjustment was reached in the Compromise of 1850. The compromise line ran the Texas western boundary from El Paso east along the thirty-second parallel to the 103d meridian, up that meridian to 36°30″ latitude, and along that line to the 100th meridian, thence down the 100th meridian to the Red River, giving us Texas’ present boundaries.

American Period

The United States obtained eastern Colorado as part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and the disputed central portion in 1845 with the admission of Texas as a state, including part of the San Luis Valley. Over the next year, an influx of slaveholding Americans in eastern Texas and boundary disputes between Mexico and the United States led the American government to provoke a war with Mexico.

Following the defeat of the Mexican army and the fall of Mexico City, in September 1847, the Mexican government surrendered, and peace negotiations began. The war officially ended with the February 2, 1848, signing in Mexico of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The treaty added an additional 525,000 square miles to United States territory, including the land that makes up all or parts of present-day Arizona, California, Colorado (including the rest of the San Luis Valley), Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. Mexico also gave up all claims to Texas and recognized the Rio Grande as America’s southern boundary. In return, the United States paid Mexico $15 million and agreed to settle all claims of U.S. citizens against Mexico.

After the Mexican-American War, US Army incursions into the San Luis Valley persuaded the Muache and Capote Utes to make a peace agreement at Abiquiú, New Mexico, in 1849. The agreement encouraged New Mexicans (recently made US citizens by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo) to settle the former Mexican land grants. In 1851, on the Sangre de Cristo Grant in the southeastern part of the valley, Hispanos established San Luis, the first permanent town in what would become Colorado. The next year, the townspeople finished an acequia, the San Luis People’s Ditch, which was the first water right in Colorado.

A number of other towns, built in the Spanish style with central plazas, popped up along Culebra and Costilla Creeks in the ensuing years, and the Conejos Grant was also settled. Despite the treaty, Utes continued to raid Anglo communities, as the influx of newcomers threatened their food supply. In 1852 the US Army built Fort Massachusetts (later Fort Garland) south of La Veta Pass, firmly establishing the American presence in the valley. The fort did little to discourage Ute raids; still, in the 1860s, more Americans arrived looking to set up homesteads on fertile lands within the valley. The Denver and San Luis Valley Wagon Road Company linked these early settlements to Denver via a toll road.

One of the new immigrants was Otto Mears, a man of great ambition who came to the fledgling town of Saguache in 1866. Mears developed what was likely an ancient trail over Poncha Pass into a toll road, linking the San Luis Valley with mining districts in South Park and the Upper Arkansas Valley. Mears also brought modern farming equipment, including a reaper and thresher, envisioning the valley as a great supplier of produce to mining camps in the mountains. Another treaty with the Utes in 1868 gave Americans near-exclusive rights to the valley, as the Capote and Muache bands—along with several others—agreed to move to a vast reservation on Colorado’s Western Slope. Mears’s vision for the valley was further realized after the Brunot Agreement in 1873, in which the Ute leader Ouray agreed to cede the San Juan Mountains to the United States. In the mountains around today’s Silverton and Ouray, prospectors found rich veins of silver and gold, and farmers in the San Luis Valley supplied them with wheat flour, potatoes, and other produce.

Conclusion

The history of the San Luis Valley is a fascinating glimpse into the hopes and aspirations of many people over the last 10,000 years. From the earliest archaic North Americans to today’s citizens if the United States, the valley is woven in a complex tapestry of history; a living mosaic of land and people. Any argument to “ownership” of the land could be easily won by the Archaic peoples, who roamed the land for over 8,000 years. The Ute tribe, caretakes for nearly 500 years, sometimes violently, at other times peacefully, have yielded the land to Europeans and their descendants, who represent a mere 4.28% of the entire history of the valley, as measured by years of human presence.

Visual Representation – Presence of Human Habitation in the San Luis Valley

Populating The San Luis Valley and Adjacent Lands, Eras, in Years:

References:

James S. Aber, “San Luis Valley, Colorado,” 2002.

Stephen Harding Hart and Archer Butler Hulbert, eds., The Southwestern Journals of Zebulon Pike, 1806–1807 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2007).

Martha Quillen, “Colorado’s Mexican Land Grants,” Colorado Central Magazine, December 1, 2001.

San Luis Valley Development Resources Group, “A. Area Description and Development History,” 2013 Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy.

San Luis Valley Development Resources Group and San Luis Valley Council of Governments, “2015 SLV Statistical Profile,” 2015.

https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/ute-history-and-ute-mountain-ute-tribe

https://www.uncovercolorado.com/san-luis-valley-colorado/

https://www.southernute-nsn.gov/history/

R. Laurie Simmons and Marilyn A. Martorano, “Guns, Fire, and Sheep: History and Archaeology of the Trujillo Homesteads in the San Luis Valley, Colorado,” Southwestern Lore 73, no. 3 (2007).

Virginia McConnell Simmons, The San Luis Valley: Land of the Six-Armed Cross, 2nd ed. (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1999